Five Ways We Undermine Efforts to Increase Student Achievement

(and what to do about it!)

by Juli Dixon

Blog Post Part 1 of 5

Thank you for the amazing response to the ignite session I provided at the 2018 Annual Meeting of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (#NCTMAnnual2018) [to view the Ignite session, go to https://www.nctm.org/Conferences-and-Professional-Development/Annual-Meeting-and-Exposition/Past-and-Future/2018-Washington-DC/ and click on the Ignite video – Juli’s talk begins at 21:40]. Based on the feedback I received I decided to write a series of posts to provide a more in-depth exploration into these unproductive practices and what to do about them. What follows is my first in a series of 5 blog posts I will share here over the next few weeks. Please submit comments, questions, and ideas so that I can work them into my responses for my subsequent posts. I am hoping that we can use these posts as a catalyst for some important dialogue here and on twitter (@thestrokeofluck).

While we are focusing on these unproductive practices here, I am also sharing related posts regarding administrators’ six spheres of influence regarding teaching and learning mathematics in a blog hosted by HMH (https://www.hmhco.com/blog/an-administrators-6-spheres-of-influence-in-mathematics-teaching-and-learning)

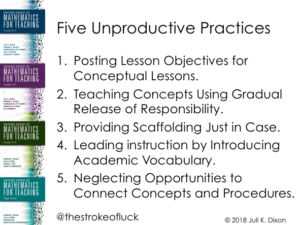

I imagine that those of you who were not at the ignite might be curious about these unproductive practices by now. Here is the slide I shared at ignite:

These teaching practices are commonplace and often required by administrators and/or districts. Many of them may have been generated from our colleagues in English language arts (ELA) and might work very well in their content areas, however, upon reflection, you will see that they are often unproductive when applied during mathematics instruction. My goals in this series of blogs are to help you to see why these practices are unproductive and also to assist you in generating a plan for what to do about it.

This post will focus on the first unproductive practice of posting the lesson objective (or essential question) for conceptual lessons. Posting the lesson objective for conceptual lessons at the start of the lesson has the potential to undermine students’ efforts to engage in sense making. What does that mean and what can we do about it?

We need to start by acknowledging that the learning goal should determine the tasks that we use and the questions we choose to support those tasks. If a lesson is conceptual in nature, like making sense of division or understanding what factoring accomplishes, then the ways students interact with the content in those lessons should necessarily be different than with procedural lessons like those focused on long division or polynomial division. The issue here is that if students are told what it is they are supposed to “discover” at the start of the lesson then the students have been robbed of the discovery process, even if that process is highly facilitated. There should be some aspect of discovery in conceptual lessons. This is not necessarily the case with procedural lessons. If a lesson is procedural, it is appropriate and even desirable to post the lesson objective at the start of the lesson (Wiliam, 2011). If lessons are conceptual, the teacher guides students to uncover the lesson objective through guided facilitation with the tasks the teacher chooses and the questions teachers use to support those tasks.

When I share this with teachers I get some push back because of the requirements that teachers must post the essential question or lesson objective a the start of the lesson. My gut tells me to respond by saying that we need to work together to change the rules! My pragmatic side reminds me that we don’t have time for this. We must adjust now and change takes too long. While we work together to change the rules to support student achievement in mathematics, we must also work together to survive and flourish within the system we find ourselves. Here is my response to that need.

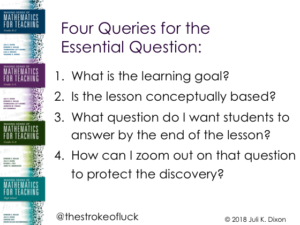

Using the Four Queries for the Essential Question is a good start. As with any lesson, our first task is to make sense of the learning goal. If the lesson is conceptually based andthere is a requirement to post the essential question or lesson objective, then a useful practice is to “zoom out” on the essential question. By this I mean to word the question or objective in a way that provides students a general idea of the goal of the lesson while protecting the inquiry that should be inherent in a conceptually based lesson. For example, if the lesson if focused on contrasting sharing into groups and making groups to divide, the posted question could be, “How can I divide in different ways?” By the end of the lesson, the student should be able to describe the difference between sharing and grouping to divide. The key here is that the student does the sense making by the end of the lesson rather than being told by the teacher what to think at the start of the lesson. We can transition our unproductive practices to be productive by keeping the learning goal and student engagement at the foreground of our planning and by critically analyzing our instructional decisions and structures. I am looking forward to continuing this conversation!

Please tweet your thoughts, comments, and ideas on this post to @thestrokeofluck

References:

Wiliam, D. (2011). Embedded Formative Assessment. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.