Five Ways We Undermine Efforts to Increase Student Achievement

(and what to do about it!)

by Juli Dixon

Blog Post Part 2 of 5

Wow – I am blown away by the response to my posted Ignite video! You can view it on the NCTM Annual website (https://www.nctm.org/Conferences-and-Professional-Development/Annual-Meeting-and-Exposition/Past-and-Future/2018-Washington-DC/) beginning at timestamp 21:40. I am also thrilled with the conversations shared on twitter (@thestrokeofluck). I didn’t know what to expect as I am relatively new to blogging, so please keep the feedback coming so I can support you to the extent I am able. I will also share the second installment related to these posts regarding administrators’ six spheres of influence regarding teaching and learning mathematics in a blog hosted by HMH within the next week or so. The first post in that series is posted here: https://www.hmhco.com/blog/an-administrators-6-spheres-of-influence-in-mathematics-teaching-and-learning.

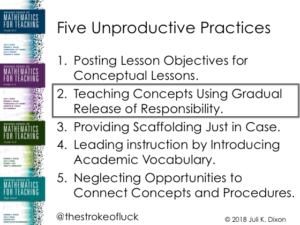

Let’s dig in to the second of Five (Un)Productive Practices.

During the Ignite presentation I said that I wanted to talk about gradual release and then gradually get rid of it. I must admit that what I shared was a bit stronger than I had planned. I guess I got caught up in the momentum of the Ignite session. I was probably still reeling from the outstanding presentations provided by my fellow Igniters. It was very stressful to watch such excellent and entertaining five-minute presentations knowing that I was going to share some ideas that were intended to make people feel uncomfortable – and I only had five minutes to do it in!

So what did I intend to say? I intended to say we need to be critical about our over-use of the classroom structure referred to more commonly as “I do, we do, you do.” This teaching technique is being overused during mathematics instruction and people are realizing it! This is a good thing, but it is not enough. In an effort to hold on to a structure that is no longer appropriate to support all aspects of teaching for rigor, people are responding by saying, “you can enter gradual release at any phase.” I can’t be the only one that finds this to be nonsense…

The entire idea of graduate release of responsibility is to begin with the teacher in control of the sense making by modeling a problem or idea (see Pearson and Gallagher (1983) for the original coining of this term in an article on reading comprehension). The teacher then moves to a more facilitated role by supporting students to engage in the task along with the teacher, in essence, replaying what the teacher has shared. Finally, the teacher relinquishes control so that students can demonstrate their understanding.

Changing the order of gradual release, or entering it at a phase where control is already relinquished is no longer gradual release! You can’t gradually release something you didn’t have at the start! OK, enough exclamation points – but this really gets to me.

With all of that said, I do believe that there is a time and place for gradual release. It is absolutely appropriate for teaching procedures. If your goal is to teach a lesson on long division or polynomial division, I strongly encourage you to model the process first, then provide guided practice as your students use the procedure with you, and finally, allow space for your students to practice the algorithm independently. The implementation of gradual release, without modification, is appropriate for procedural lessons. What about lessons more conceptual in nature? This is where gradual release needs to be replaced, not revised.

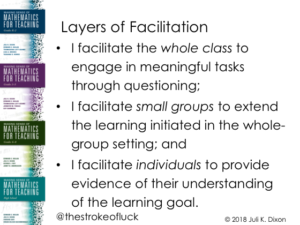

My colleagues and I in DNA Mathematics (#DNAmath) developed a lesson delivery structure that is appropriate for use with conceptual lessons. I will introduce it here. However, if you want a more comprehensive exploration, I invite you to check out the Making Sense of Mathematics for Teaching series (https://www.solutiontree.com/products/product-topics/dixon-nolan-adams-mathematics-resources.html).

The Layers of Facilitation describe a lesson structure that is more student-centered than Gradual Release of Responsibility. The goal of this structure is to privilege classroom discourse while maintaining a focus on the learning goal for the lesson. The teacher implements a task through the use of whole-class discussion. The teacher supports students to engage in the task through questioning. Full-class discussion around a problem is followed by students all working on the next problem (or set of problems) in concurrent small groups with the teacher pushing into groups to provide support through questioning and to collected evidence from student responses. Finally, individual accountability is supported as students work on problems on their own to provide evidence of where they are relative to the learning goal for the lesson.

The key here, again, is that the students are doing the sense making and the teacher is supporting them to meet the learning goal through the task that is chosen and the questions that are used to support the implementation of that tasks. As stated in the first post, we can transition our unproductive practices to be productive by keeping the learning goal and student engagement at the foreground of our planning and by critically analyzing our instructional decisions and structures. I am looking forward to continuing this conversation!

Please tweet your thoughts, comments, and ideas on this post to @thestrokeofluck

References:

Pearson, P. D. & Gallagher, M. C. (1983). The instruction of reading comprehension. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 8, 317-344.