Five Ways We Undermine Efforts to Increase Student Achievement

(and what to do about it!)

by Juli Dixon

Blog Post Part 3 of 5

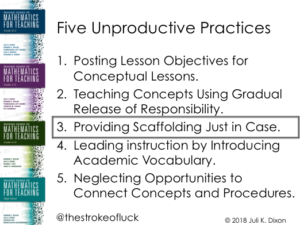

As promised, I am providing the third in a five part series of posts unpacking the Ignite session I provided at the NCTM Annual a little over a week ago. You can view the Ignite on the NCTM Annual website (https://www.nctm.org/Conferences-and-Professional-Development/Annual-Meeting-and-Exposition/Past-and-Future/2018-Washington-DC/) beginning at timestamp 21:40. While you are there, you should check out all of the Ignite sessions – they are worth the time!

I am especially excited to discuss this third potentially (Un)Productive Practice because of my personal focus on supporting students who struggle. You can learn more about how I developed first-hand knowledge related to students who struggle by reading about my family’s story at www.astrokeofluck.net. This will also clarify the genesis of my twitter handle (@thestrokeofluck).

Now back to the topic of this post – scaffolding. In education, scaffolding describes supports provided to students to assist them in meeting a learning goal. So what does scaffolding have to do with supporting students who struggle? It has everything to do with supporting students who struggle when the answer to the question, ”How do you provide differentiation?” is “By scaffolding.” This becomes an issue when the scaffolding is provided “just in case” students might need it rather than “just in time” when students demonstrate the need.

Just-in-case scaffolding creates issues of both access and equity. When scaffolding is provided before students have the opportunity to make sense of a challenging task without the extra help, students are inhibited from developing productive perseverance. All too often, so much support is provided through the initial scaffolding that the cognitive demand of the task is significantly decreased (Boston & Wilhelm, 2015). If this sort of scaffolding is provided for students who struggle, then these same students are denied access to cognitively demanding tasks. When access is denied, equity becomes an issue.

So how do we provide differentiation that is equitable? We can still provide differentiation through scaffolding. The key is to provide the scaffolding just in time rather than just in case students need it. Just-in-time scaffolding helps to develop productive perseverance by allowing students to engage in demanding tasks and then assisting them to maintain the engagement when they struggle by providing support through teacher questioning.

This is where I wish I could show a classroom video to model what I mean by providing scaffolding just in time. We will need to imagine the classroom instead. Consider a class of students in grade 7 who are tasked with solving the following problem:

Alex used up all of the money she had saved from her lawn care job to buy a skateboard. She then borrowed $17 from her mother to go to the movies with her friends. After she went to the movies she bought a soccer ball for $15. She borrowed that money from her mother as well. Alex keeps track of her money in her notebook. What should she write in her notebook to indicate her balance now? Explain your reasoning.

What are your thoughts as you read the problem? Are you thinking that the wording might be confusing for your readers who struggle? Are you thinking about issues students often have when computing with integers? Those are all legitimate thoughts. It is what we do in response to those thoughts that either supports or inhibits students’ achievement. It is all about the scaffolding.

Often, when I observe teachers using tasks like this with learners who struggle, I see scaffolding in the form of teachers unpacking the word problems to the point that the task becomes an exercise. It might sound something like this:

Teacher: Would the $17 be positive or negative?

Students: Negative.

Teacher: What about the $15?

Students: Negative.

Teacher: What do we do when we add negative numbers?

The cognitive demand of the task is greatly diminished by this “scaffolding.” The students are no longer left to make sense of the context and determine the operation to be performed. The teacher is providing supports for students in anticipation of a struggle. This is providing just-in-case scaffolding.

In contrast, imagine a classroom where the teacher provides space for students to do the sense making. It might sound something like this:

Teacher: (reads the problem to the students) Class, spend 2 minutes thinking about this problem and then share your ideas with your partner.

(Teacher waits 2 minutes before circulating the room to listen to discussions of students)

Student: (addressing teacher) We don’t know how to solve it.

Teacher: What is the problem asking?

Student: What Alex should write in her notebook to show how much money she has.

Teacher: What do you know?

Student: We know that she spent all her money and then borrowed money from her mom.

Teacher: Now work with your partner to see how you might represent the money she borrowed. (Teacher walks away).

What you probably notice is that the teacher provides processing time for students to do the sense making. When students indicate a struggle, the teacher provides just enough information so that students can re-engage with the task without lowering the cognitive demand of the task. Which classroom image most closely represents the opportunities you or the teachers you support are affording students? How would you describe your classroom?

As with my other posts, the changes in practice I suggest have the goal of ensuring that the students are doing the sense making and the teacher is supporting them to meet the learning goal through the task that is chosen and the questions that are used to support the implementation of that tasks. As stated in the first post, we can transition our unproductive practices to be productive by keeping the learning goal and student engagement at the foreground of our planning and by critically analyzing our instructional decisions and structures. In this post, I added an additional intention to access and equity by withholding scaffolding until it is necessary. I am looking forward to continuing this conversation!

Please tweet your thoughts, comments, and ideas on this post to @thestrokeofluck

References:

Boston, M. D., & Wilhelm, A. G. (2015). Middle school mathematics instruction in instructionally-focused urban districts. Urban Education, 52, 829–861.